Five Ways to Bind Your Book

The curious thing about writers and writing websites is that they spend a lot of time talking about writing and how to write and what to write, and reviewing books that other people have written, but there doesn’t seem to be much out there about the ins and outs of physical books. So since you seem to have enjoyed last week’s post about how to tell the age of a book, I thought it might be interesting to look at the different ways that they can be bound.

There are a number of ways to bind the pages into a book, all with their own pros and cons.

1. PERFECT BIND

Most paperbacks these days are perfect bound because it’s cheap and easy. Where in other styles, the pages need to be sewn together before they are attached to the cover, perfect binding does not.

In this method, the pages are stacked together into a neat block then the edge that will be fixed to the spine is roughened up. This gives the paper a little more texture to that when it is glued, it will stick to the cover. Once it is glued and the cover is firmly attached, the three remaining edges are trimmed as required so that they have that lovely uniform look.

Some of the benefits of perfect binding (or case binding, as it is also known) is that it is cost effective. They’re popular in indie publishing because of the lower pricing, while still retaining a professional look. Because they are lower in cost, it’s preferable for smaller print runs or even print-on-demand titles.

The problem with perfect binding is that it’s not ideal when it comes to hardbacks. I checked my bookshelf and my more modern hardbacks all seem to be perfect bound (some have used head- and tail-bands to hide it). I have a special Face of Disapproval for this kind of thing but it’s understandable: you get to sell a nice hardback look but you don’t have to pay such high production costs. My beef with case bound hardbacks is that they just don’t last as long. I don’t want to pay two or three times the price for what is essentially paperback quality with a hard case slapped on the outside. If I buy a hardback, it’s a special book I want to last, but I’ll stop now before I trail off into a rant!

Perfect bound books don’t sit flat against a surface either. This isn’t a problem for novels, but for reference books, cookbooks, or notebooks, it might not be what you are looking for.

Because of the tightness of the binding, you do have to be careful when typesetting a book you plan to bind this way. I have seen a number of indie authors and beginner typesetters who set their pages with equally sized margins on both sides. When perfect bound, this can make the text seem like it isn’t central. If you are typesetting a book that will be perfect bound, your gutter (the margin nearest the spine) needs to be a little wider than the outside margin so that the words are clear and the text looks central. It looks strange when you are reading the PDF, but it makes the print book look like the text is in the centre of the page.

If you use Lulu, IngramSpark, or KDP, their paperbacks tend to be perfect bound. It looks professional and is low cost, but be careful to check whether whoever is printing your book is using high quality materials. If they’re not, the glue will dry and flake eventually, causing the pages to fall out.

2. SMYTH SEWN

This is a much more durable method, the sort you’d use on high-quality books you want to last a lifetime. In this case, the pages are printed several pages to a sheet of paper and folded into signatures (usually 8, 16, or 32 pages each). The pages in each signature are sewn together then all of the individual signatures are sewn together to create what’s called a ‘book block’. Essentially, it’s a bunch of smaller booklets that get sewn together to create the full book (but without a cover yet). The book’s endpapers (and I love nice endpapers) get one page glued to the outside of the book block and the other page is glued to the cover. On the whole, smyth sewn books tend to be hardbacks because of the way they are sewn. It doesn’t look good glued to a paper cover.

The sewing is far more durable than glue, and higher quality. If you look at the spine of a smyth sewn hardback from above, you can see how the pages sort of group together in bunches at the spine. Those are the signatures. If you open the book wide enough to the centre of the signature, you might be able to see the thread.

Smyth sewn books aren’t as popular as they used to be and understandably so. They cost a lot more to produce, reducing profit margins, and they’re higher quality so people aren’t going to need replacement copies as quickly.

Nevertheless, they have both style and durability benefits of you are less concerned about the cost. First off, because they are sewn, not glued, they sit flat against the surface when you open them. This is great for journals, reference books, and sketchbooks. They’re also just way more durable. Paperbacks are easily torn and damaged and it’s easy to pull the odd page out, but smyth sewn books are much sturdier. They’re ideal for books that you want to last, books you love and treasure, or books that are frequently loaned out and not always taken care.

It’s not clear how KDP, IngramSpark, or Lulu bind their hardbacks so the option for smyth sewn hardbacks may not be available for indie authors from the major self-publishing companies (cost aside). Nevertheless this binding is more pleasing to the eye, it’s just that the cost means very few of us will be lining our shelves with them though.

3. SADDLE STITCH

Personally, I think it would be hilarious if all Westerns were saddle-stitched but that’s just my odd sense of humour. This kind of binding is very common, you probably see it all the time without even realising.

Fun fact: the reason it’s called saddle stitching is because the pages are draped over a saddle-like bit of apparatus to be fixed together.

So saddle stitching is where the pages are gathered together, folded down the middle, then stapled together with the folded ends of the staple on the inside of the book. Sometimes a couple of stitches will be used instead, but normally it’s staples. There are usually two staples in the spine but for a larger book (A4 as opposed to A5) more staples can be used.

It’s quick, easy, and cheap: you print your book, trim it, fold it, and whack a couple of staples through it. However, once you get past about 64 pages, it doesn’t work very well. This method is most effective for booklets and magazines rather than full length tomes.

4. WIRE/SPIRAL BOUND

Wire binding is another method that doesn’t really fit professionally published novels. It does have its uses though, and as authors, it’s helpful to be aware of it in case it proves useful for any side projects you might like to try.

Wire binding is pretty straight forward. The chances are that you’ve done school projects this way or owned notebooks bound this way.

The text is printed in a similar manner to the perfect bound book. The stack of pages is then put through what is, effectively, a glorified hole punch, and wire rings used to secure the pages together. There are two ways to do this. One is that you use a series of C shaped pieces of wire which hold the pages (wire bound), the other uses a single spiral shaped piece of plastic (spiral bound), though you can use wire too.

Spiral binding looks a little less professional, you may remember school projects held together that way, but it is more durable than simple wire binding. In the overall pricing scheme, it’s less than perfect binding but you lose that nice bookish look.

This kind of binding is good for instruction manuals, workbooks, and some people like it for notebooks. The reason it made it to this list is that many authors not only publish fiction, but write about the writing craft and if you decide to create a work book to go with your book, or your course, or whatever else you might be up to, spiral or wire binding is an option that costs less than perfect binding but is more durable and allows more pages than saddle-stitching. If you really hate the exposed wire, it is possible to have a case cover put on to make it look a little nicer.

5. COPTIC BINDING

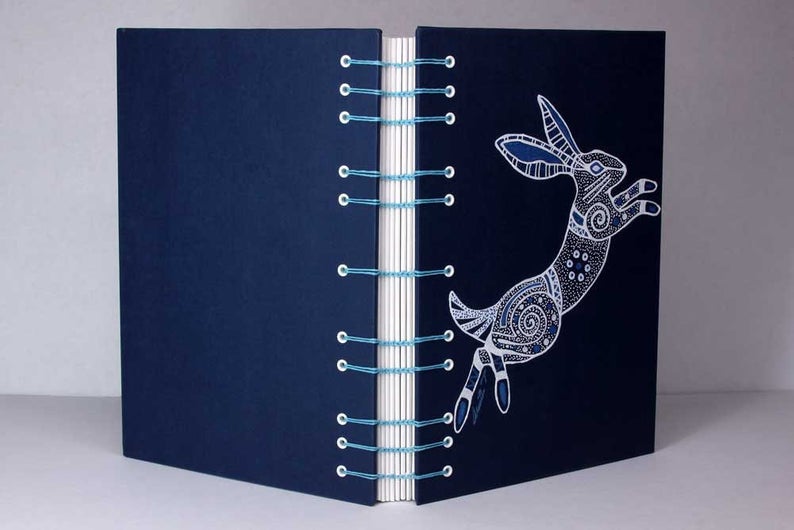

I’ll be honest with you, this is only here because I think it looks pretty. You only really see it used in fancy, handmade notebooks, though I’m sure we could argue for a revival of its use in our books.

Coptic binding is an ancient way to create books, used by Egyptian Christians as early as the 2nd Century AD, right up to the 11th Century. With this method, there are various different kinds of stitches that you can do, often for decorative purposes as the stitching is not covered by a spine. The signatures are sewn together, then the whole work is chain stitched across the spine to hold it together and fastened to the hard casing on the front and back of the book which provides protection for the pages inside.

It is popular in handmade notebooks and sketchbooks because the stitching on the spine can be very beautiful and, because of the way it is sewn, the book will open flat against the surface it is resting on. You can find the particularly pretty example above, and others like it on Etsy (credit where credit is due!).

If you want to try making your own notebooks, or are looking for something a little unique for a journal or sketchbook, this is a good place to start. Just be aware that the exposed spine makes it more vulnerable to water damage than other bindings might be.

SO THERE YOU GO

. . . A brief introduction to book binding methods. If you made it this far without glazing over too much, congratulations! Not to worry you too much, but you might be running the risk of becoming as geeky as me (I really must remember to tell you about the Chained Library!).

As authors, it’s all very well writing books and handing them over to a printer, but I believe it’s important to know a bit more about how a physical book comes into being once the words are all in order. Indie authors in particular may benefit from a little knowledge about the kinds of bindings available as it will help you to decide the balance you want to strike between quality, durability, and price for your work.

It’s also just really interesting. There are a multitude of other ways to bind books by hand that I haven’t even touched upon but, if you’re interested, that can be a discussion for another day.

YOUR TURN

- What’s your favourite binding on books?

- If you had limitless resources and it wasn’t going to cost your fans a fortune, how would you have your masterpiece bound?