5 Ways to Tell the Age of a Book

My dad and I have a game in which we look at a book (we’re allowed to touch it and sniff it too) and can tell you when it was published. My worst estimate was twenty years out one time but, on the whole, we can date it well within a decade. It’s a great party trick but anyone can do it with the right knowledge and a little practice.

To help you out, here are five ways to tell the age of a book just by looking at it.

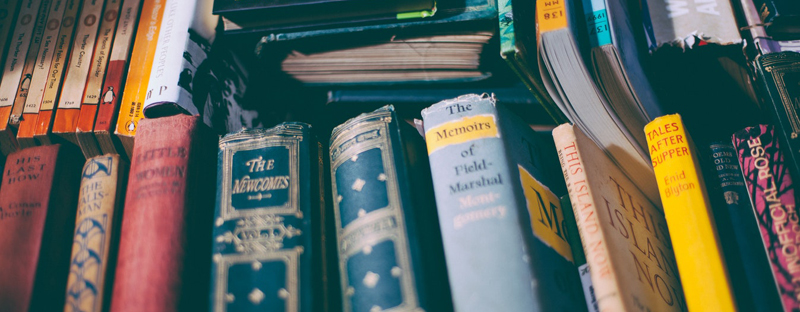

1. THE COVER

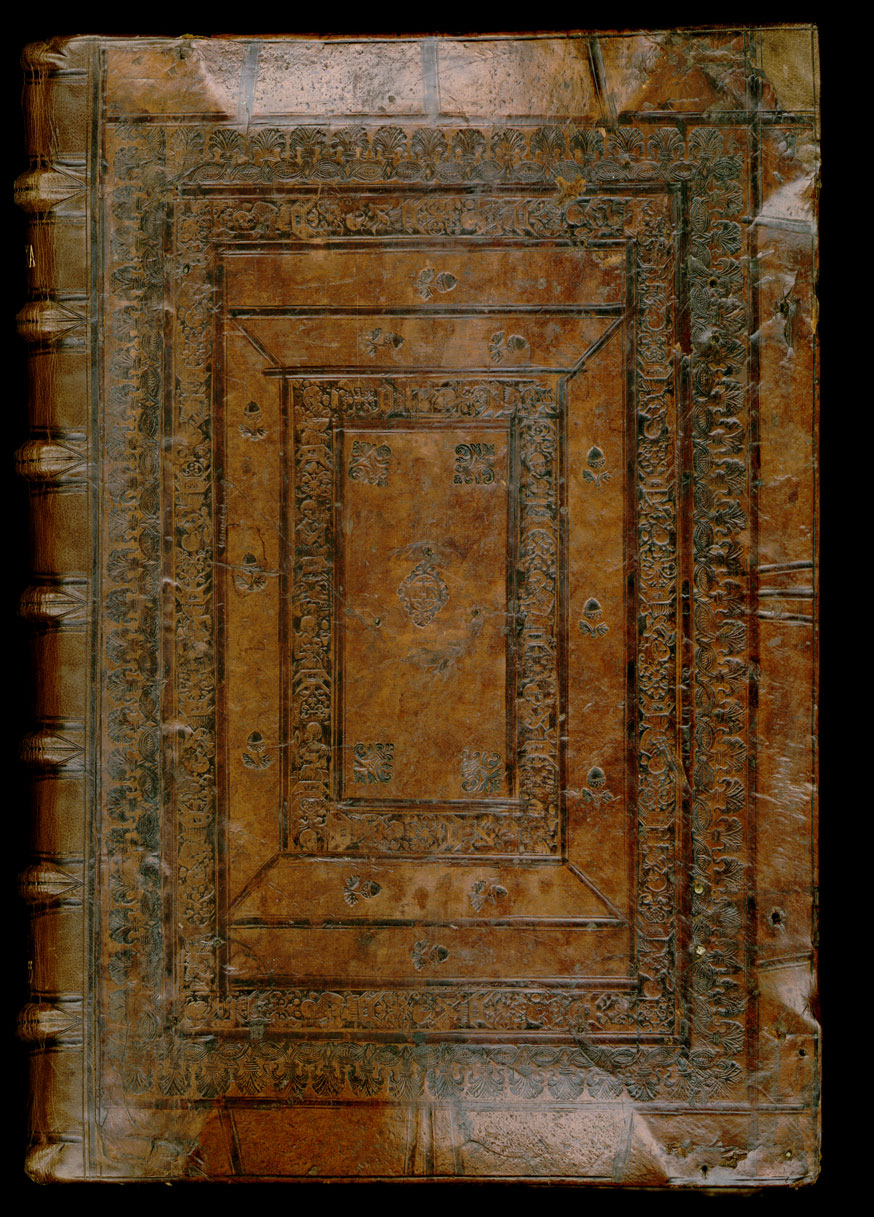

When it comes to telling the age of a book, you can at least begin to judge a book by its cover. Different materials have been used to bind books down the ages and there are ways of telling what sort or era the books were bound in by the materials used. The older the book, the more likely it is to be calf (or other leather) or vellum. The difference in material made the Victorian books in the library stand out like a sore thumb.

Decoration has also varied down through the ages. This can be another telltale sign of when a book was bound. In the Renaissance, when the printing press was first coming into its own, books were still a luxury item and would often have quite elegant covers. There would be embellishments on the covers and even the spines, often in gold. A good example would be the Gutenberg Bible, which was printed 500 years ago.

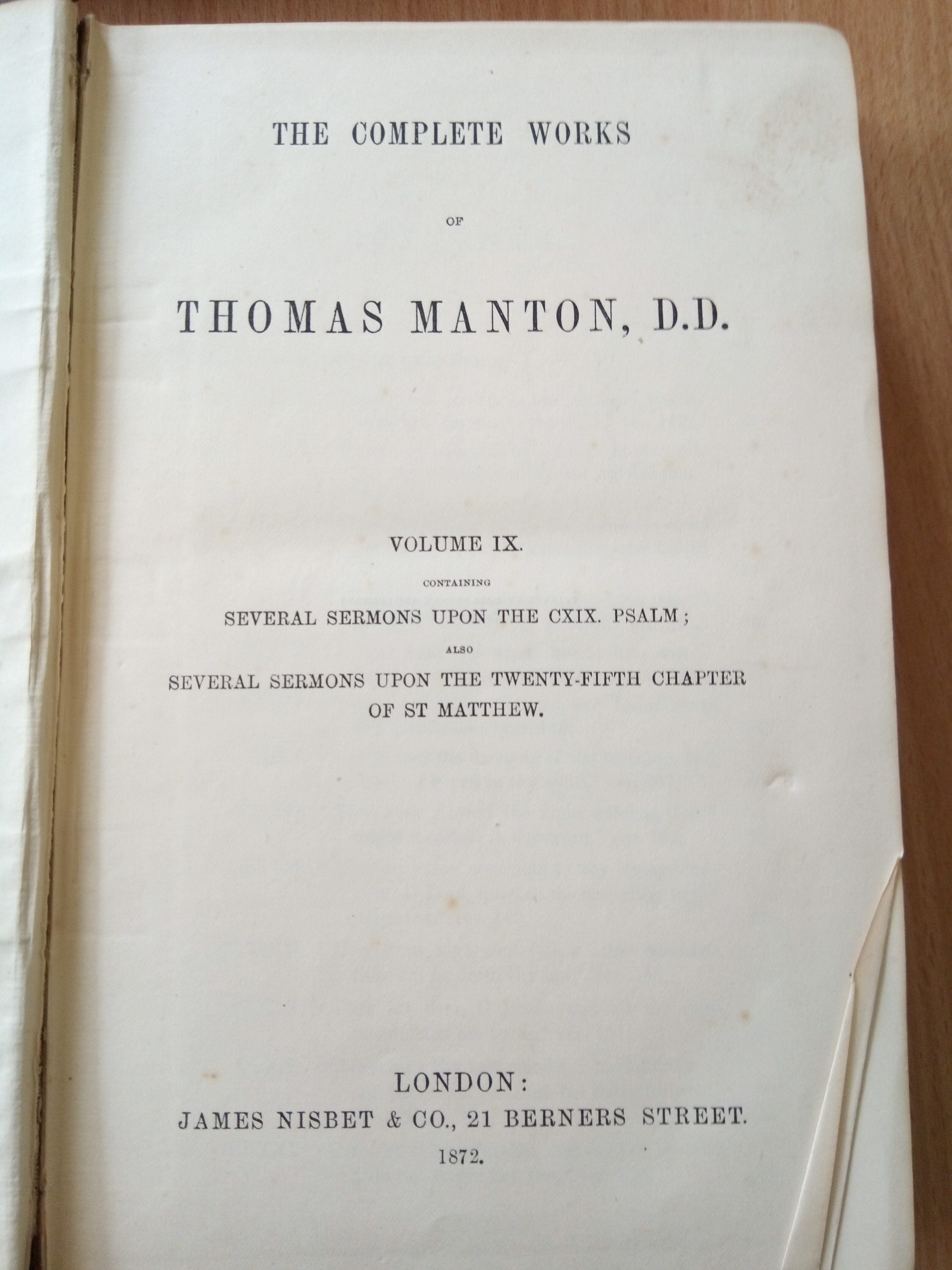

More recently (and closer to the sort of thing we mere mortals are likely to come across) the Victorians were very sturdy and practical in their covers for reference books. On the whole, they went for plainer bindings and would often match a whole set so that it looked good in the gentleman’s study or the family library. Another feature was their use of cloth over board for covers, not just leather bindings.

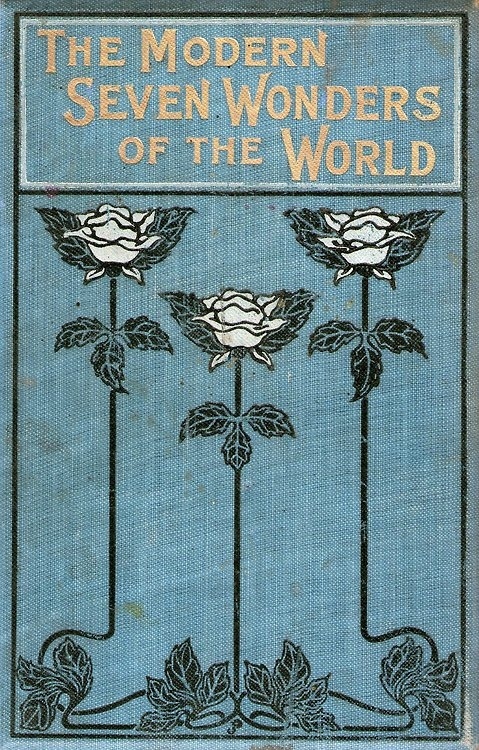

However, their novels and poetry books can be much more elaborate, with patterned borders, illustrated scenes on the front, and even semi-gothic fonts. The style varies depending on the publisher and the genre but you can generally tell a Victorian binding on non-fiction books by their sturdy practicality, and their fiction books from the art style and the font.

Post-Victorian, the fonts begin to change again and it moves from a not-quite-art deco style to an art-deco style, then to that stylised WW2 and post WW2 posterised look. From there on, you’re probably familiar with cover art styles.

I say all this, but thinking about it, it’s hard to explain exactly how you know from the cover. The more books you handle and the more you will know. It’s important to remember, however, that though the binding of a book can be a good clue about its era, it’s not infallible. The Victorians in particular were ones for rebinding older volumes either to match their libraries or to preserve already damaged books, and they weren’t fussed about trying to mimic the original.

2. INSCRIPTIONS

Sometimes when you open a second hand book, it will have an inscription in the front. On most occasions, I don’t look at the first page because inscriptions normally include a date and that’s cheating.

You can, however, tell a little from the handwriting. The ink, how faded it is, and the handwriting itself can give you clues about the period.

Pre-1900s, you’re more likely to have a cursive font in a blue-ing or brown-ing ink (or at least, that’s my experience). The pen style changes with time and by the mid 1900s, the writing is much less cursive and the ink less faded. The names and the language used can also help sometimes but it’s not a reliable way to date a book unless you combine it with the other factors.

3. THE SPACE BETWEEN SENTENCES

Because of the way printing presses developed, older books generally have larger spaces between the end of one sentence and the beginning of the next. If you have ever been frustrated by people who use a double space at the end of every sentence, it’s a quirk left over from the days of typewriters.

It carried over from old printing styles where the width of an M (em-quad) or an N (en-quad), depending on the publisher, was left after a full stop. It prevented the page from looking too cramped. This was partly to do with aesthetics and partly to do with fonts.

You can read more about it here (and in many other places) but if you’re wondering about a book, the spaces between the sentences will tell you whether the book is recently printed or not.

4. INDENTED PRINT

By indented print, I don’t mean that there is a space at the beginning of each paragraph or that the margins are particularly wide, it just means that you can see the texture of the print from the other side of the page. I’m sure it has a fancy name.

Granted, this is a more difficult thing to see on thicker papers, but if you run your fingers over the text on a book printed recently compared to a book that’s a couple of hundred years old, you can feel the difference.

Why is this the case? I’m not sure and the internet wasn’t much help but I would guess it’s to do with printing techniques. Back in the day, printing presses used to stamp the page on so my best guess is that at some point this changed, enabling a smoother process that didn’t leave impressions in the paper.

Because I’m not sure about the reason, I’m not sure about the dates either. I think probably all the books I’ve seen with the text impressed have been pre-1900, maybe earlier.

5. FONT

Hand written and illuminated books are usually pretty clear about their age but when it comes to printed text, the font can still tell you about the book. It’s only now that we have everything digitalised that it has become easy to design and use whatever obscure fonts we like. In the early days of printing, this was much more difficult.

Early on, every page was carved into a plate or block and effectively stamped onto paper. Even when moveable type was invented, you had a big box of letters that you arranged into the text for each page. As a result, there wasn’t a massive amount of variance in the fonts used and, if you are acquainted with typeface, you will be able to recognise the older style.

Font cannot be taken alone though. Old style fonts are still used in books today, but, combined with some of the things mentioned above, it can be an indicator of when your book was published.

A LAST NOTE ON DATING BOOKS

It must be said that I am not a historian or an expert of any sort. Dating books is a game my dad and I have played for a very long time and I thought it might be interesting to give a little insight into how we do it.

The reason I didn’t include the smell of books in the list is because it’s not a verifiable measure. Of course, it can tell you that the book is old or new, well kept or damp, and whether any of the past owners might have been smokers (pipe or cigarette), but years don’t have a precise scent that they leave embedded in the pages. Despite this, it does help somehow.

In truth, these are small parts of how you might guess at the age of the book but I couldn’t tell you how we really do it. There are times we hardly even look at the book, breathe it in, then tell you with a year or two. Other times we’ll compare notes on it for a good few minutes then debate our differing guesses. Often, I’m not sure how I know, I just do.

If you take these tips and practice, you could learn to date books too but at the heart of it is this: if you spend time around books, if you really like them, you will know them.

YOUR TURN

- Do you have any quirky, book related skills?

- Have you ever tried to date a book by handling it and smelling it? How accurate are you?

- Do you have any other tips for knowing when a book was published?